Broadcast Hysteria: Orson Welles’s “War of the Worlds” Lie That Fooled America

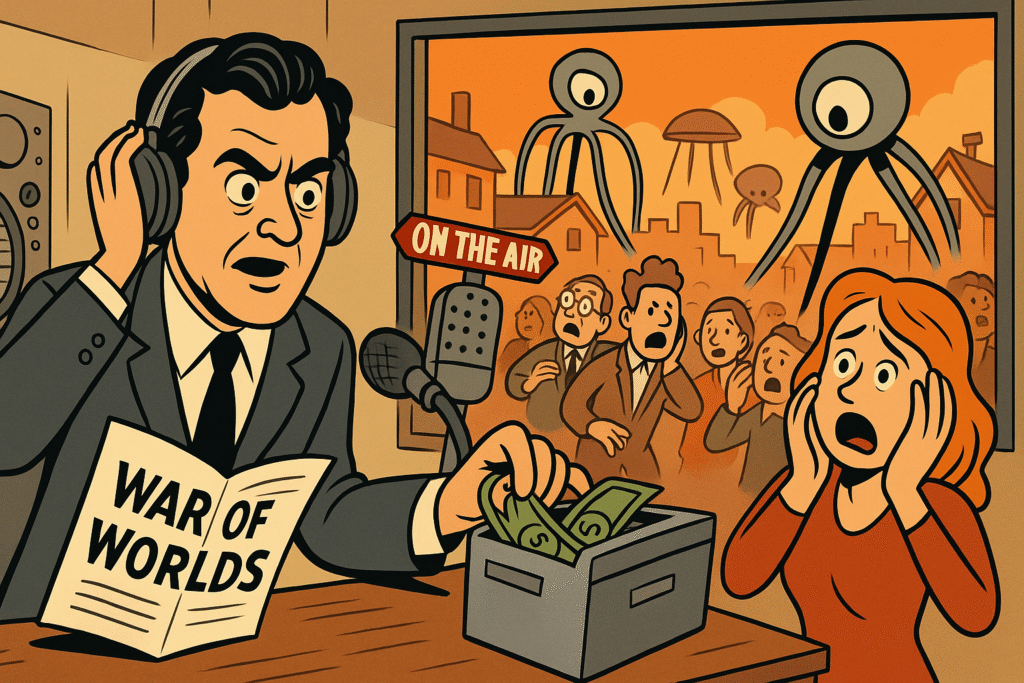

On the foggy evening of 30 October 1938, a 23-year-old Orson Welles broke into America’s living rooms with bulletins of Martians marching on New Jersey. Listeners who tuned in late heard only panicked “reporters” and roaring tripod machines—and some briefly believed every word. The broadcast—quickly branded The War of the Worlds scare, the “lie that fooled America”—has since become the classic case study in how mere words and sound can bend reality. history.comsmithsonianmag.com

Fast-forward to the 2020s and the medium has changed, but the spell remains. In May 2023, an AI-generated photo of an explosion near the Pentagon rocketed across social platforms, rattling stock markets before officials could tweet the truth. apnews.comtheguardian.com

Nine months later, thousands of New Hampshire voters received a robocall that flawlessly mimicked President Biden’s voice, urging them to “save” their ballots and stay home—a deception that drew criminal charges and a potential multi-million-dollar fine. theguardian.com

Whether it’s a 1938 radio drama or a 2024 deep-fake, these episodes hammer home the same lesson: well-crafted language, delivered through trusted channels, can jolt publics, move money, and sway elections before skepticism catches up. Researchers warn that cheap AI tools are set to supercharge such linguistic sorcery, making tomorrow’s misinformation storms faster, cheaper, and harder to spot. wired.com

Table of Contents

1. Setting the Stage: Radio, America, and a Perfect Storm

On 30 October 1938—a drizzly, pre-Halloween Sunday—tens of millions of Americans did what they always did at dusk: gathered round the radio. The medium was their living-room hearth, pulsing out Roosevelt’s Fireside Chats, swing music, and cliff-hanger serials. Newspapers remained influential, but radio’s immediacy had begun eating into print advertising and political clout, sparking a bitter cross-media rivalry. newyorker.com

Several conditions primed the public for alarm. Europe was careening toward war; headlines about Hitler’s annexations kept anxiety high. Radio carried breaking news bulletins about looming conflict, so listeners were conditioned to treat abrupt program interruptions as urgent and true. Meanwhile, sound-effect technology had become remarkably convincing—thunderous explosions, sirens, even “static” that mimicked a failing transmission. Into this tinderbox stepped a 23-year-old prodigy named Orson Welles, determined to stretch the limits of radio storytelling. neh.gov

2. Inside the Mercury Theatre: How Fiction Masqueraded as News

Welles’s Mercury Theatre on the Air normally adapted literary classics in straightforward dramatic style, but that week he wanted something edgier. He and writer Howard Koch relocated H. G. Wells’s The War of the Worlds from Victorian England to contemporary New Jersey, then framed the story as a series of live news flashes. The broadcast opened with dance-hall music, only to be “interrupted” by breathless reports from Grover’s Mill, where “cylinders” had crashed. Actors adopted the clipped diction of field correspondents; engineers layered muffled screams beneath crackling short-wave static.

Crucially, CBS inserted a disclaimer at the top of the hour, and Welles broke character near the end to remind audiences it was fiction. Yet many tuned in late, missing the warning. In 1938, listeners could not “rewind” or scan social media for context; real-time comprehension depended on trusting the voice in one’s speaker. The result was immersive realism, not deceit—but it blurred the line between art and reportage so thoroughly that confusion felt inevitable. en.wikipedia.org

3. Newspapers Fan the Flames: Manufacturing the Panic Narrative

The panic legend did not erupt spontaneously from living rooms; it burst onto breakfast tables the next morning. Competing papers trumpeted headlines such as

“Fake Radio ‘War’ Stirs Terror Through U.S.”

and recycled sensational anecdotes: motorists fleeing Manhattan, churchgoers collapsing, expectant mothers going into labor. Editors claimed switchboards jammed “from coast to coast,” neatly omitting that most calls were simply curious, not hysterical. vanityfair.com

Why exaggerate? First, scare stories sold papers at a time when circulation was sliding. Second, depicting radio as reckless served the industry’s economic self-interest; if broadcasters could spark chaos, advertisers might stick with the safety of ink. Third, the narrative supported congressional rumblings for tougher regulation of the new medium. In other words, the most influential “Martians” that week were newspaper moguls waging a turf war. mediamythalert.comwellesnet.com

4. Myth Busting with Data: What the Evidence Really Shows

Hard numbers slice cleanly through the fog of folklore. The C. E. Hooper ratings survey, conducted while the show was still on air, queried 5,000 households nationwide; only 2 percent were tuned to Mercury Theatre, and none believed they were listening to news. The vast majority were enjoying the comedy-variety hit The Chase and Sanborn Hour. en.wikipedia.orgsnopes.com

Later, psychologist Hadley Cantril estimated that 1.7 million listeners felt “disturbed,” but scholars have shredded his methodology: he conflated mild concern with full-blown panic and relied on newspaper clippings (already inflated) to recruit interviewees. The result was a feedback loop: sensational press accounts shaped Cantril’s sample, and Cantril’s study then legitimized the press narrative. lincolnmemo.commediamythalert.com

What about the most lurid tales—suicides, stampedes, mass illness? Archival police logs and hospital records show no corroboration. FCC files contain roughly 600 complaint letters, most polite, some cranky, but few describing personal terror. The Commission concluded no law had been broken and issued only a caution that future dramas be clearly identified. wellesnet.comhistory.com

Even the oft-repeated story of New Jersey farmers firing shotguns at a water tower rests on third-hand retellings; local papers of the day never mention stray bullets. In historian A. Brad Schwartz’s phrase, the greatest casualty was truth, not human life. newyorker.com

5. From 1938 to Today: Lessons on Media Hype and Misinformation

The saga endures because it dramatizes a perennial fear: that new technology can hypnotize the masses. In 1938, that technology was radio; today, it is social media, deepfakes, and algorithmic newsfeeds. The mechanics remain eerily similar:

- Dramatic content triggers emotional response.

- Amplification by secondary outlets (then newspapers, now digital platforms) spreads the most extreme anecdotes.

- Audience metrics are misread or ignored.

- Regulatory or political actors exploit the crisis narrative to pursue their agendas.

In the hours after the broadcast, Welles faced a wall of flashbulbs and apologized “deeply” for any distress—yet he also noted, with sly irony, that the press seemed more panicked than the public. youtube.comwellesnet.com

Eighty-plus years later, the War of the Worlds myth is a masterclass in critical consumption: check primary data, question sensational framing, and remember that anecdotes—however vivid—are not trends. The Martians never landed, the nation never stampeded, and the real lie was a headline built to sell extra editions. Recognizing that truth arms us against every new wave of viral panic, whether it arrives by radio static or 5G bandwidth. newyorker.com

Conclusion – Lie That Fooled America

From the crackling vacuum-tubes of 1938 to today’s pocket-size supercomputers, the technology of storytelling has changed beyond recognition—yet its spell remains the same. Orson Welles’s War of the Worlds showed how a voice cloaked in authority can make fiction feel like fact, if only for a moment. Ninety years later, AI-generated images, synthetic voices, and algorithm-boosted posts replay that lesson at lightning speed, jolting markets, muddying elections, and shaping public emotion before skepticism can find its footing.

The thread connecting Grover’s Mill to our social-media feeds is not the medium but the message: words, when expertly framed and widely amplified, possess the power to redraw the boundaries of reality. That power is neither inherently good nor evil; it is a tool—one that demands craftsmanship from creators and vigilance from audiences.

Our best defense is the same today as it was after Welles’s closing curtain: cultivate curiosity, verify before sharing, and teach media literacy as a civic skill, not a niche hobby. If we do, the next astonishing bulletin—whether about Martians, markets, or politics—will land on informed ears, and the line between story and truth will stay clear. In an era of instant echo, that clarity is our most reliable shield.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) – Lie That Fooled America

Did Americans really panic when they heard the 1938 broadcast?

Not on a national scale. Contemporary ratings show only about 2 % of households were tuned in, and most listeners either dismissed the story as fiction or quickly changed stations for confirmation. The myth of nationwide terror was amplified by newspapers eager to criticize a fast-growing rival medium.

How many people actually believed the Martian invasion was real?

The best modern scholarship (see A. Brad Schwartz’s Broadcast Hysteria) estimates tens of thousands felt genuine alarm—far below the “millions” trumpeted in 1938 headlines. Early surveys such as Hadley Cantril’s lumped mild concern together with outright panic, inflating the numbers.

Was anyone hurt or killed because of the program?

No verified deaths or serious injuries have ever been documented. Stories of heart attacks, suicides, or mobs firing at water towers are anecdotal and lack primary evidence. Police logs, hospital records, and FCC files show only scattered confusion and a few angry phone calls.

Why did newspapers exaggerate the panic story?

Radio was siphoning both audience and advertising dollars from print. By portraying broadcasters as irresponsible purveyors of hysteria, newspapers protected their market share and bolstered arguments for stricter federal regulation of radio content.

Did the U.S. government punish Orson Welles or CBS?

No. The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) investigated, found no law violated, and issued only a caution urging clearer disclaimers for future “news-style” dramas. Welles offered a public apology but faced no fines or bans.

What parallels exist between the 1938 broadcast and today’s misinformation?

What parallels exist between the 1938 broadcast and today’s misinformation?

Both rely on three ingredients: realistic presentation, rapid distribution, and trusted voices. In 1938 that meant authoritative radio announcers; today it can be deep-fake audio, AI-generated images, or viral social-media posts. The core lesson—verify before you amplify—remains unchanged.

Could a similar hoax succeed now?

Technically yes, but media literacy, instant fact-checking, and multiple information channels make large-scale deception harder. That said, short-lived shocks still occur, such as the 2023 AI-generated photo of an “explosion” near the Pentagon that briefly rattled stock markets.

Where can I listen to the original broadcast?

A high-quality recording is freely available through the Library of Congress and many podcast apps. It runs just under an hour and includes Welles’s closing announcement clarifying that it was all make-believe.

Has a modern “lie that fooled America” emerged in the digital era?

Yes. In May 2023, an AI-generated image of an explosion near the Pentagon went viral, briefly shaking stock markets before officials debunked it. The hoax echoed the 1938 incident—showing how a striking image or clip can become a 21st-century “lie that fooled America.” apnews.comtheguardian.com

Source List – Lie That Fooled America

- A. Brad Schwartz, “https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/infamous-war-worlds-radio-broadcast-was-magnificent-fluke-180955180/” – Smithsonian Magazine (6 May 2015).

- A. Brad Schwartz, “https://www.vanityfair.com/culture/2015/04/broadcast-hysteria-orson-welles-war-of-the-worlds” – Vanity Fair (27 Apr 2015).

- C. E. Hooper Company background page – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/C._E._Hooper.

- Hadley Cantril, The Invasion from Mars: A Study in the Psychology of Panic – Princeton UP (1940) https://press.princeton.edu/books/paperback/9780691138262/the-invasion-from-mars.

- A. Brad Schwartz, Broadcast Hysteria: Orson Welles’s War of the Worlds and the Art of Fake News – Hill & Wang (2015) https://us.macmillan.com/books/9780809040575/broadcasthysteria.

- Adrian Chen, “https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/09/04/the-fake-news-fallacy” – The New Yorker (4 Sept 2017).

- Dan Milmo, “https://www.theguardian.com/books/2025/mar/17/the-big-idea-do-we-worry-too-much-about-misinformation” – Lie That Fooled America, The Guardian (17 Mar 2025).

- David Klepper, “https://apnews.com/article/pentagon-explosion-misinformation-stock-market-ai-96f534c790872fde67012ee81b5ed6a4” – Lie That Fooled America AP News (23 May 2023).

- “https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/article/2024/may/23/biden-robocall-indicted-primary” – The Guardian report on the 2024 deep-fake Biden robocall (23 May 2024).

- Lee Ann Potter, “https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2003/fall/war-of-worlds.html” – National Archives Prologue article on FCC letters after the broadcast (Fall 2003).

- David Klepper, “https://apnews.com/article/artificial-intelligence-hamas-israel-misinformation-ai-gaza-a1bb303b637ffbbb9cbc3aa1e000db47” – AP News (28 Nov 2023) on Gaza-war deep-fake images.

- Library of Congress audio: “War of the Worlds” broadcast (30 Oct 1938) – https://www.loc.gov/item/2004560356/.